By Nimi Princewill.

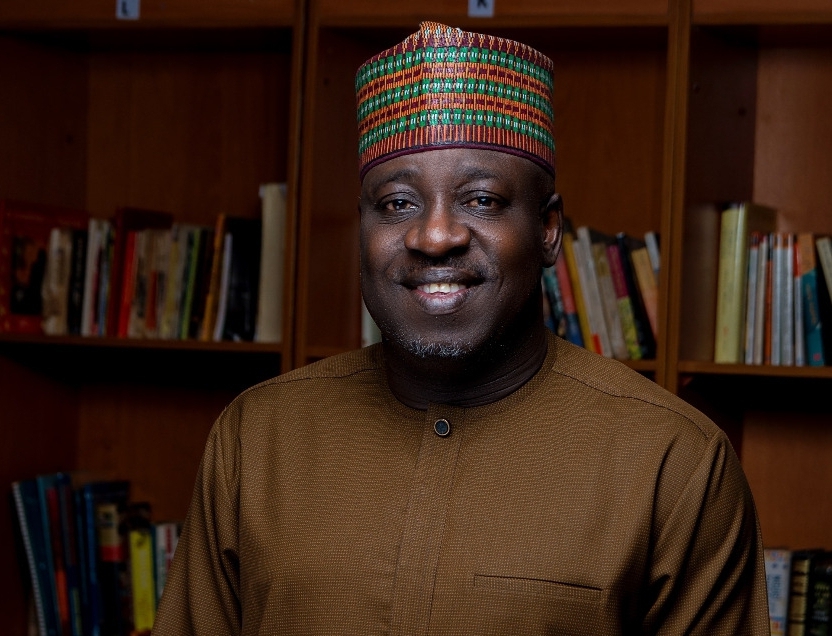

Former minister of youth and sports, Mallam Bolaji Abdullahi, today clocks 50. In a commemorative interview to mark the occasion, he tells his story to a team of INSIDER reporters.

What were your memorable childhood recollections?

I grew up in a very loving family. My parents are still alive. They aren’t educated. They were very poor, but what they lacked in money, they more than made up for in love of their children and invested everything, especially on the moral instructions that they had. I used to tell people that I don’t know what they were thinking when they named me Bolaji, because Bolaji means someone who grew up in prosperity, and these were poor people naming their child Bolaji.

I started school with a gathering of children under a tree in front of the palace of the village chief. I did not step into a classroom until I was in primary two. Some Italians building the road that led to Kaduna from Kontagora in Niger State found out that there was no school in the village we lived in, which was located at the outskirts of Kontagora, so they donated a block of classroom to the village. That was how we moved from our school under the tree to a primary school. I spoke english for the first time when I was eleven.

My first four years of education was in Hausa. Even the English language we learnt was taught in Hausa.

My mother always talks about a story of how I died and they dug a grave to bury me before I changed my mind and refused to die again.

All the factors that points to a great future; a good family in terms of material comfort, educated parents who are really dedicated to ensuring their children gets the best education, and so on, were not available for me. So I like to tell people that I’m probably the twelfth wonder of the world, that a child from such a background could grow up to become as educated as I am.

What were the early influences on your life? Were there people you aspired to be like?

I never aspired to be anything. I never had an inspiration. I was growing up in a village, so who will I aspire to be like? The first time I had the consciousness to aspire to be like anything was when I got into secondary school.

I went to Government Secondary School, Kwali, Abuja. I had earlier attended a community secondary school in Kwara State but at Form 2, I decided I was not going to attend the school again because I was always coming first. I was a village champion, so I told my dad I wasn’t going to attend the school again.

My dad, knowing how difficult it was to get me into the community school since I didn’t pass common entrance exam, told me if that was my decision, then it meant I obviously didn’t want to continue schooling again because he had no money to send me elsewhere. I said yes, if it wasn’t Mount Camel College, I wasn’t interested, because, for me at that time, it was the best school in the world.

In a bid to raise money, I secretly started working as a bus conductor in Ilorin. I always heard my dad boasting to his friends that no child of his can ever be a conductor, labelling them as Indian hemp smokers. I’d look at him and smile. He didn’t know a bus conductor was living under his roof. When he later found out, I got the beating of my life, then I was shipped off to Kwali in Abuja to live with my uncle who feared I was becoming a tout.

I attended a government secondary school in Abuja, but lived in the junior staff quarters in the Federal Government College, Kwali, where my uncle worked as a chief driver, so I always came in contact with store keepers and librarians who were my role models. I just wanted to finish secondary school and get a job in Federal Government College, Kwali, as a staff. That was all I wanted in my life, nothing more.

When I was in Form 4, I was close to one of the librarians who lived in the quarters. He always took me to the library. As I was about to enter Form 5, I realized I had finished reading all the books in the library. The librarian was shocked and asked me what I wanted to do with my life. I told him I think I’ll love to be one of the people who wrote the books in the library. So he left and came back with a ream of papers and a box of Bic biro and told me to write. I don’t think I wrote anything anyone would consider to be serious, but that was when the light of what I eventually became was lit. Unknown to me, that was the begining of a career.

I cleared my GCE and WAEC exams with distinction, then I heard the Federal Government College, Kwali, was recruiting, so I went to apply since that was my ambition. The principal went through my credentials and called me. He said he would not employ me because if he does, God will not forgive him. He said with this result, I needed to go to school. That was how my life transformed.

How will you describe your parents?

These two people are the greatest influence in my life, and I consider them to be the greatest human beings that I know. Even as a young child, I realized that most of the things they taught me are the things I continue to fall back on even now when things get difficult.

My father, for example, will tell you ‘if you say something and they’d have to tell you to come and swear that you’re telling the truth, then you’re not a human being’. He believes there isn’t a more contemptible human being than such person. My mum would always say life is never a straight line, there will always be ups and downs. I’ve gone through difficult moments in my life, and every time, I keep referring to these things that they taught me. If you see anything today that you admire about my character, the credit should go to my parents.

Can you tell us about your days in Unilag?

I went to the University of Lagos because I wanted to study Mass Communication. At that time, Unilag was the foremost institution for Mass Comm. Before then, I tried to join the Army because at the Nigeria Defence Academy, you didn’t have to pay school fees. I was to join the 40th regular course of the NDA. I passed the exam and went for the interview but they didn’t admit me, they said I was color blind. Maybe, they were right, because I think I’m color blind. Then I went to Federal School of Arts and Science, Suleja, in Niger State, again because I didn’t have to pay school fees. It was while doing my A-levels at the college that I gained admission into Unilag.

My days in Unilag were quite momentous. In 200 level, I was the editor of the university newspaper. Then, in 300 level, I was the editor of the university magazine. I remember one occasion when we took a course named Advanced News Reporting and Writing.

I did a story and submitted to the lecturer. The lecturer read my story in the class and said there was no need for me to come for the exam. Right there, he gave me five points. That was a course people would be happy not to carry over to the final year.

As a student journalist, our newspaper once made a story about ‘Admission Fraud in the University of Lagos’, just a day before the institution’s matriculation. When the headline came out on matriculation day, the university was mad!

The management ordered a retraction to be published the following day, stating on the front page that the story was false in its entirety and we regret any embarrassment the story must have caused the university authority. I strongly refused a retraction because the story was true and I wrote it myself.

I asked the university to show evidence that the story was false. I threatened to resign as editor if a retraction is carried. They went ahead and published the retraction on the front page of the newspaper. I called my colleagues and we agreed not to circulate the newspaper. The next thing, a panel was set up, saying that I acted in a way that caused embarrassment to the university, and I should show cause why I should not be rusticated from the university.

I faced the panel and put them in a very serious ethical dilemma. Some of the lecturers started pondering on why they should punish me for doing what they taught me without undermining the foundation of the Mass Communication Department. I don’t know how they ended it, but that was the last I heard of the case. That of course, made me popular, then I contested for president of the department and won. It was constant battle till I left.

What will you say about campus politics today compared to your time?

Student unionism in my time had a strong ideological foundation. We saw our role as student leaders as that of challenging the government and tertiary institutions to do the right thing. It’s painful when I see student leaders these days hanging around politicians.

Again, like I said the last time I came to the University of Ilorin, how come successive generation of students from the institution are graduating and are unable to find employment, and employers are saying they are unemployable and that what they’ve been taught is not relevant to the requirement of the industry, yet I’ve not heard any student leader or a group of students challenge the university for teaching them what the industry say is not useful to them?

Year in, year out, no student leader has said ‘there must be something the university is not doing right that make employers say we are unemployable’.

They just carry on with focus on the certificate. Student leaders should have the intellectual capacity to engage with the institution.

How was your early years in Lagos, considering that you weren’t born there?

I grew up in rural Niger State, where life was slow and predictable. I had never been to Lagos until I gained admission into Unilag. A friend of mine who was familiar with the city told me vehicles don’t stop for anybody in Lagos, so I prepared my mind and told myself I was fit enough.

The moment our bus arrived Lagos and I heard ‘Unilag, come down’, I immediately jumped down from the moving vehicle and found myself rolling on the ground with bruises. The only trouser I had which I was wearing got torn in the process. The bus conductor and everyone in the vehicle was wondering why I jumped out like that. It was later when I became more experienced, I realized the techniques of jumping out of a moving vehicle.

Another occasion I remember was when I went to pray in the mosque. When I was done praying, I discovered my slippers were gone. Since I didn’t have money to replace it, I had to walk from Ikeja to Agege barefooted. But I think one of the best training opportunity any young man starting life could have is to go to Lagos. It will toughen you up, and the level of exposure that Lagos gives you is unequal in Nigeria. Lagos played a very important role in my formative years and part of what made me who I am today.

As a journalist, what were your most challenging assignments?

I had some memorable assignments which were not only challenging but career defining. The one I remember most was during a riot in Warri, when the Urhobos and Itshekiris were fighting over the location of a local government headquarters and they were killing each other in dozens. As a young reporter, I was sent to cover the event. It was a very difficult assignment for me, trying to stay alive and at the same time trying to get my story. You’d meet someone today and the person would say come back tomorrow and get my photograph, and by the time you get there the next day, the house has been burnt down.

The best story I did at that time covering the Warri crisis wasn’t the fight itself, but the fact that in the end, I found a church, I think it was the God’s Kingdom Society, GKS, where the Urhobo women, children, the Itshekiri women and children laid side by side, sharing food together as refugees. These were people that were killing each other, but found a common bond to live together.

The second one was when I went undercover to work in a factory in Lagos. There was a Chinese factory in Lagos which I discovered always had a long queue of people every morning whenever I took the route to work.

So I inquired and learnt they were casual workers who weren’t staff of the company but queued up there everyday hoping to get a job for the day. It sounded interesting to me, so the following day, I went to join the queue and I was lucky to get the job.

I entered the factory, worked for a whole day and spoke with the staff and people working in the place; some who had lost a hand, some an eye working at the factory. I went home and wrote a story. The Lagos State Government shut down the factory after I published the story because of their inhuman practices.

The last one I remember was when Shehu Musa Yaradua died. He was to be buried in the afternoon, so I had to get to Katsina before he was buried. I hired a photographer and since there was no internet, you can imagine how difficult it was sending the photograph so the story could make the front page the next day, and added to the fact that we didn’t have a circulation van.

Incidentally, a Guardian reporter came and went to the same photographer I hired and the guy just simply sold my pictures to the reporter who, unfortunately for me, had a circulation van. The story appeared on The Guardian front page the next day and Thisday (the agency I worked for) published the story without a photograph.

It was like the end of the world losing to a competitor. None of my excuses were good enough to the publisher who said I didn’t send the photographs because I wanted to take the money meant for the photos. I quickly interjected and told the publisher that even before he could abuse me, I had thoroughly abused myself because I knew no excuse was good enough but he should never again accuse me of stealing.

Bewildered, he looked at the General Manager, asking if he could imagine this ‘thing’ (referring to me) telling him not to say it again. He said he’d give me a query, I told him not to bother. I wrote my resignation letter. They were shocked. The publisher asked if I had another job, I said no. He asked if I wanted to ruin my life, I said, well, it was my life and I would not accept being accused of stealing.

He pleaded with me to rescind my resignation, wondering how I was going to cope in Lagos without a job. He told me Thisday was going to open a South African bureau and he was planning for me to be the international correspondent and now I wanted to throw all of that away. I told him my mind was made up and I left. I went home and cried. I was jobless with rent to pay, a daughter and a wife. Things were very difficult until I later found a job at the Hallmark Newspaper, now Business Hallmark.

You worked briefly with the African Leadership Forum (ALF), how will you describe your time in the civil society and what was the experience like?

While working with the Hallmark Newspaper, I went to cover the PDP convention in Jos, the one that produced Obasanjo as the presidential candidate, when I was told that the African Leadership Forum, an African-based NGO needed a Director of Publication; I declined. But the person who told me about it kept insisting I give it a try, so I reluctantly obliged.

When I met the ALF Director, he surprisingly asked me to write an essay to prove I could write. You can imagine the insult, but somehow, I wrote the essay and when he read it, he asked how much I wanted to earn. I said to myself, I’d mention an amount of money he can never pay, so I emphatically stated N30,000!

Without negotiation, he said I should resume on Monday. That was how I started working at the ALF. The ALF was a great learning experience. It gave me the right exposure. Funny enough, the first country I visited while working with the ALF was South Africa. I traveled extensively with the Forum until I got so tired of traveling.

I later became Director of Programmes at the ALF, running Democratic Leadership Training workshops when Thisday called me about two years later to return, this time as Deputy Editor of the Sunday Newspaper. Six months later, I became Deputy Editor of Thisday itself, just less than three years after quitting as a reporter.

If I hadn’t taken that decision to quit on principle, I’d probably still be there now, growing through the ranks. Principles come with a heavy price tag. It doesn’t come cheap.

Was there a time as a journalist you wrote a story that put you in trouble with the authorities?

Ah, yes. While at Thisday, there was a weekend we didn’t have a cover story for Monday. Everyone had run out of ideas until the publisher pitched an idea to us: ‘The Four Men Behind Abacha’.

We were so excited. We did a profile of Al Mustapha, Gwanzo, Diya and Husseini and published as our cover story. By Monday morning, the Directorate of Military Intelligence visited our office and asked who wrote the story. Everyone quickly pointed at me.

Myself, the editor and one of my colleagues were ordered to immediately report in Apapa and we were held for days. What we didn’t know before we published the story was that at that time, the Army had put Diya, Abacha’s second in command, under surveillance for coup plotting, so they thought he planted the story to divert attention from himself.

The Head of DMI at that time in Apapa asked who my father was. I told him my father was a poor tailor in Ilorin. He asked about my mother, I said the same thing. He asked if I had a wife, I said no. Then he said, ‘now listen to me, if you don’t have a passport, I’ll get you a passport so you leave Nigeria. But if you must continue to write this type of nonsense, I will shred you and flush you down the toilet and nobody will see you again. If you think I’m joking, try me’. This was the time journalists were disappearing.

They kept asking about who gave us the story. They believed there was more to it than what we were writing. Eventually, they freed us, although we were compelled to report daily at DMI which we did consistently until Abacha died.

Do you miss being a Columnist?

Absolutely. Though, I later left to be Special Assistant, Special Adviser, Commissioner and Minister, the best title I like most is when people call me editor. I feel more proud to be called an editor than any other title I’ve acquired in my life, because that’s who I am, a journalist.

Even while as Minister, I met people who identified me as Bolaji Abdullahi of Thisday, especially the Northerners who like to refer to one particular mischief I played back then as a columnist.

Pa Abraham Adesanya, who was a Yoruba leader at that time, called Thisday to complain about a story. I was the only one in the office, so I took his call and introduced myself as Bolaji Abdullahi. Surprisingly, he asked, ‘what kind of name is that? How can you be Bolaji and be Abdullahi at the same time and say you’re Yoruba?’

I told him I’m Ilorin. He then asked the meaning of Bolaji, I told him I speak Yoruba doesnt mean I’m Yoruba, that I’m Ilorin. He said I’m yoruba, I insisted that I was Ilorin, the same way you can’t say that the Americans are British because they speak English.

The following day, I reported the conversation verbatim. All the Northerners went crazy attacking the mindset of the Yorubas. They interpreted it as though the Yorubas were saying people didn’t have the right to bear Muslim names anymore. Pa Adesanya called the next day, saying he didn’t mean it that way. I told him I only published what he said. Many years later, whenever Kashim Shettima, the former Borno State governor sees me, he jokes by asking if it’s Bolaji Abdullahi or Abdullahi Bolaji.

When I came to Kwara to serve as Special Assistant to the then governor, Saraki, I went through a difficult moment. I missed writing, I missed journalism. I went to the late Justice Mustapha Akanbi and told him I didn’t feel like continuing with the SA job and that I wanted to go back to Lagos to journalism. He said he understood how I felt but said the work I was doing here was also important.

He said, if by being here, I am able to get just one child who would ordinarily not get education to go to school, it was more than 10,000 newspaper articles. He said, if by working in government I am able to influence the government to give water to a people that would ordinarily not have access to water, it was more important than all the articles I was writing. That cured me of my nostalgia.

If you weren’t a journalist, what would you have loved to be?

I would have been an actor. The day I left for Kaduna for the NDA interview was the same day the National Festival for Arts and Culture opened in Lagos, and I was to represent the FCT in a solo performance because I was also into acting. In fact, while in secondary school, I was part of a drama group that went from school to school to do theatre for money, that was how we were surviving.

My dilemma at that time was between going to Kaduna for the NDA interview or to Lagos for my performance at the Festival. My uncle didn’t give me the chance to decide, he chose Kaduna over Lagos. It was also at the National Festival that Zach Amata was discovered. Maybe if I had gone to Lagos for the National Festival, my life would have probably taken a different trajectory. But I’m happy I ended up as a journalist.

What do you consider as the highpoint of your career, both as a journalist and politician?

I became a Minister at the age of 42. I remember how I’ll sit in the Federal Executive Council made up of about 40 people and I’ll look at myself, remembering where I’ve come from. I’ll look around the room, this is the highest decision making body for Nigeria. Out of 150 million people, 40 people are sitting in this room and deciding what happens to Nigeria and I am one of them. That was very important to me and I consider it to be a unique privilege.

However, the most memorable moment of my career which I continue to hold very close to my heart was the time I spent in Kwara as Commissioner for Education. That was the most important assignment I’ve ever held.

I consider myself extremely lucky. I’m going to be 50 on August 12. I left University at the age of 25. In 25 years or so, I’ve worked as a journalist, I’ve worked in the civil society, I’ve worked in government at the state and federal level, I’ve worked in the national party. God has given me this unique opportunity to amass a broad portfolio of experience in my working life in a way that he has not done for many people.

What notable challenges did you face while driving reforms as Commissioner for Education?

I started by visiting schools, chasing teachers into the classrooms until one day, I got to a school and saw a teacher teaching a child how to measure without a ruler. The teacher was measuring one centimeter with the full stretch of his fingers, then I realized that having one bad teacher in the classroom was worse than having no teacher at all. That was when I stopped chasing teachers into the classroom and settled down to real work.

I decided that the teachers should write an exam based on what a Primary Four pupil is expected to know. It was tough getting about 21,000 teachers to agree to write the exam. I had to sign an agreement with them that no single teacher will lose his or her job as a result of the exam. After the exam, I received an email of the results. Out of almost 21,000 teachers who wrote the exam, only 75 of them scored up to 80%. I was paralyzed, I couldn’t get out of bed.

Since we had promised not to sack, we had to device other strategies of tackling the problem. I can say with confidence that within three years, some of these teachers who had failed the exam became star teachers because they weren’t bad in themselves, they failed that exam because their own education failed. Their primary education failed. Their secondary education failed. They probably ended up as teachers in the first place because no other institution will be willing to take them.

But many of them who were willing to learn were given the opportunity and we deviced all kinds of strategies to help them. And I’m proud to say that before I left office in 2011, many parents had withdrawn their children from private schools back to public schools.

As Commissioner for Education, one of the key achievements people still remember you with is the Every Child Count policy. What led to the introduction of that policy?

If my parents needed money for me to go to school, I would not have gone to school. Today, the quality of education that a child gets appears to depend on the social and economic standing of the parents. The richer you are, the better the education your child can get.

I realized we cannot build our country that way because the worst form of injustice is inequality. The principle of the Every Child Count policy is that every child should be given the same opportunity, regardless of the economic and social standing of his or her parents, because I’m a product of that.

While driving that policy as Commissioner, there were reports that you had to do so many hard and unexpected things like going to schools on a bike to catch absentee teachers, slapping a teacher, etc. How true were these stories?

After I declared to run for governor last year, I heard people saying I once slapped a teacher while as commissioner. I then asked, this teacher they claim I slapped, did she evaporate into thin air after I ‘slapped’ her? Because how come she hasn’t come forward to say she was slapped? Does she have a husband? When she got home and told her husband she was slapped, what did he do? Or did I slap her in the dark? How come nobody has come forward to say how I slapped the teacher?

Educational reforms are particularly challenging. When pushing for education reforms, there’d be so many losers. You can’t expect such people to be happy with what you’re doing. So it’s expected to hear all sorts of stories.

How has the Every Child Count Policy fared since you left office?

A couple of days ago, I read that the state government shut down about 22 illegal private schools because they did not meet the registration requirements. But unless a school constitutes a present danger to the lives of the children, the worst of private schools are still better than many of our public schools. So why are we not shutting down our public schools?

It’s all about service delivery, decentralization and accountability. Who cares about all these things in the public schools? Who cares if the children are making progress or not? Who are they accountable to? So, it’s a wrong approach to say we’re shutting down private schools because they didn’t meet the requirements, when some of the worst schools you can think of are public schools.

We only shut down schools during my time as Commissioner because of exam malpractices or if the school structure was injurious to the children.

What has your relationship been like with Dr. Saraki after the election?

Predictably, it was difficult. I was hurt by what happened. But we still have a relationship. Our relationship is not dependent on politics. As far as politics is concerned, I haven’t had the opportunity to sit down to review and decide what to do moving forward, but that has nothing to do with my personal relationship with him.

My dad taught me something. He said, if someone does a favor for you and the same person later does wrong to you, you should always try to remember that favor the person did for you. We’ve been together for about sixteen years, won’t there be a day he’d do something that would hurt me in those sixteen years?

___________________________________

Note: INSIDER Newspapers wishes to exert its right as the copyright owner of this interview. No part of it should therefore be used or quoted without appropriate credit given to the publication.